Although Goodyear only first took on their 12-year Wolves shirt sponsorship at the start of the 1990/91 campaign, the relationship between the two giants of the city – or town, as it was back in those days – is one which was founded around a century ago.

Having first started its globalisation programme with the purchase of a Canadian plant in 1910 and a London branch in 1913, Ohio-based Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company began by importing its products into the UK.

However, protectionist tariffs after the First World War made importation unprofitable, and a site for a permanent British factory had become a priority, with Wolverhampton – a town where car makers such as Sunbeam, Star and Guy Motors were already well-established – and the disused works of enamellers MacFarlane and Robinson on Stafford Road, making the perfect location.

Work got underway to prepare the area for the arrival of Goodyear, as deputy mayor, Alderman Willcock, laid the first brick of the new tyre factory’s landmark chimney stack, late in 1927, allowing business to begin.

The Wolverhampton plant, together with the plants in Canada and Sydney, Australia, were the first by Goodyear to be built outside of USA, with the location of the UK headquarters situated on what was then the edge of the urban area, and offered the opportunity for expansion over the years.

But it was not just Wolverhampton that was benefitting from the introduction of one of the world’s biggest tyre manufacturers setting up a home in the West Midlands. During that time, many other companies were doing the same – Michelin chose Stoke-on-Trent and Dunlop moved into Birmingham.

In the decades that were to follow, the Goodyear plant became one of the largest employers of the town, almost to an extent that you would have been hard pressed to have found a family in Wolverhampton who did not have at least one member who was a current or former employee.

While outside of the working hours, the company also served as a focus of social and sporting activities for the thousands of staff and their families, and it was here where the link between Wolves and Goodyear was founded – through its people.

For Jim McKinnon, former Goodyear vice-president and CIO, the company – like it was for so many employees – was a family affair.

“My dad worked there before I did,” he said. “A lot families worked there. I was second generation, but I know people who were third or even fourth generation, so the company had a family atmosphere.

“As with most families, football was always a big part of the workforce. At the factory, you had your Baggies, Villa and Walsall supporters, but the majority of the workers were Wolves fans.

“There was always some sort of relationship between Goodyear and Wolves, because they were only down the road from each other. Goodyear was the major employer in the town and Wolves were the team.

“The success of the team on the pitch at Molineux definitely had an effect on the productivity of the factory. One of the sayings in the old days was, ‘If the Wolves are doing well, then the factory production would be doing really well’.

“Everyone in the factory would be pumped up and motivated if Wolves were winning matches.

“People around the city get a bit down if Wolves aren’t doing too well and it’s still a bit like that today. It was a bit like that after the last-minute goal from Man United the other week – supporters would be going into work a bit flat afterwards.”

From the glory days of the 1950s to the darkness of the 1980s, Wolves had retained strong links with Goodyear. There was a point in the late 80s – at a time where the club were well publicised for carrying out training sessions on the Molineux car park – where the players would sometimes use Goodyear’s facilities to prepare for matches, due to the company’s ‘Work League’ pitches being some of the best in the area.

The start of the 1990s – after the 80s had seen Wolves almost twice drop out of business – brought a fresh start to the club and to Wolverhampton.

With lifelong Wolves supporter Jack Hayward in place as the new owner, he immediately went about funding the extensive redevelopment of a dilapidated Molineux into a modern all-seater stadium, but with finances needed to get the club out of the Second Division and into the top-flight, Wolves turned to a close ally for support.

“It’s not clear how the relationship started,” McKinnon explained. “In that did Wolves contact Goodyear or did Goodyear contact Wolves. However, it seemed an obvious partnership with Goodyear a major employer in the town and having a tradition of providing sporting activities for their families.

“Since 1928, Goodyear had sponsored many successful football teams in the Works League, and over the years strong relationships had been built between footballers and coaches at Wolves and Goodyear. I remember one time, Steve Kindon was injured, and he went down and trained with the company team to regain some fitness.”

At the time of the sponsorship, McKinnon was part of the finance team at Goodyear, but his career with the company had seen him start from the bottom before ending up at the top.

Working at the firm for 40 years, McKinnon, a Wolverhampton local, who is now a trustee with Wolves’ Compton Park neighbours Compton Care, started out as an IT intern after obtaining two degrees in Maths, and after two decades in IT, he moved to finance, before switching back to IT and eventually finishing his tenure as global vice president and CIO for Goodyear.

“I personally had various finance leadership roles in the 90s, including Treasurer Goodyear GB, and know that the sponsorship with Wolves was excellent for building business relationships, with the hospitality facilities being used pre-game for meetings with customers, suppliers and other business partners, such as bankers and actuaries, as well as for employees to watch a game.

“Wolves players occasionally visited the offices and factory and met the employees, which was always well received, as the majority of workers would be loyal Wolves supporters.

“I spoke with John Richardson, who was the managing director and finance director for the early years of the contract with Wolves and he looks back very positively about the sponsorship, in that it provided excellent media coverage for Goodyear with Wolves challenging for promotion to the Premiership and also with success in the FA Cup.

“I think the 90s was a good era for both Wolves and Goodyear because the factory was doing well and we were making about 25,000 tyres-a-day, and although we didn’t win the play-off semi-finals against Bolton or Crystal Palace, as well as the FA Cup runs and reaching the semi-final against Arsenal, they all provided good TV coverage, which ultimately benefitted the company.”

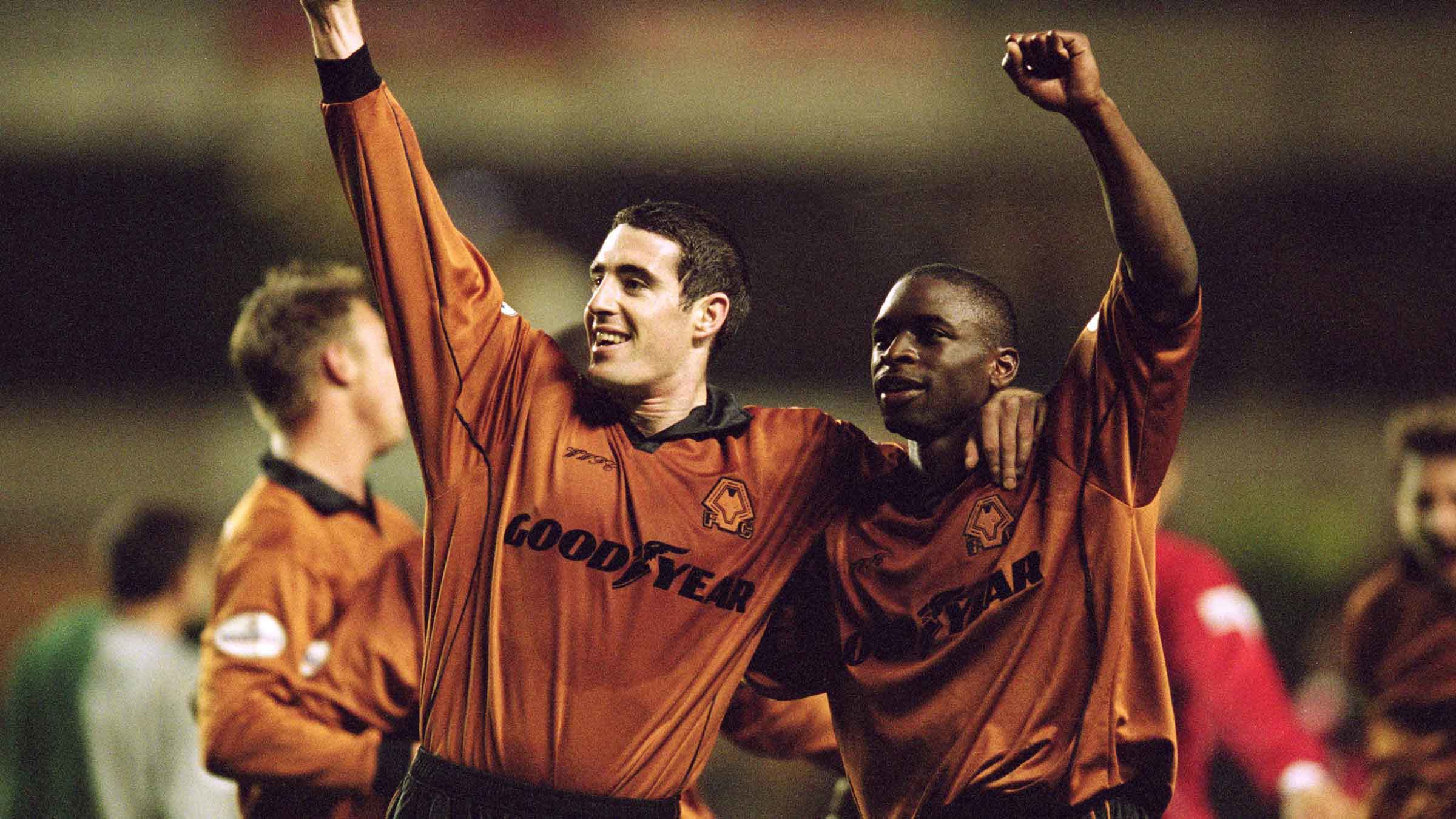

Despite falling short of top-flight promotion and that trip to the old Wembley Stadium for either a play-off final or an FA Cup final, the 1990s is one that is always looked back on fondly by the majority of Wolves supporters, and Goodyear was there every step of the way.

With the company’s logo boldly printed on the front of some of the most popular and iconic gold and black offerings to have been worn in the club’s history.