Sunday (15th September) marked the 60th anniversary of what for many Wolves fans of the older generation is the most unforgivable action ever executed by a board of directors of a football club – the dismissal of Stan Cullis.

Historian and author Clive Corbett tells the story of what led to the greatest manager in Old Gold history being removed from his post.

***

Wolves undertook a brief Caribbean tour of Barbados, Trinidad and Jamaica in the last week of May 1964, playing Chelsea five times (winning 3-1 and 4-2, and losing 3-2, 2-0 and 3-0), along with victories over Trinidad (4-1) and Jamaica (8-4), and a draw with Haiti (1-1).

Back home they began 1964/65 with just one draw from the first seven league games, a situation exacerbated by the unwelcome absence of Stan Cullis. The sequence started with losses at home to Chelsea (2-0), and away to Leicester City and Leeds United (both 3-2). The day before the defeat at Elland Road, Cullis had become unwell at work and was ordered by his doctor to take a few weeks’ rest. After a 1-1 draw in the return match with Leicester, there followed three more setbacks – at home to Arsenal (1-0), and away to West Ham United (5-0) and Blackburn Rovers (4-1).

Just over a fortnight after Cullis had started his brief break, on Monday 14th September, he was back at his desk preparing for the visit of West Ham, as reported by Phil Morgan in the Express & Star: “After a week at the seaside Wolves boss Stan Cullis returned to his Molineux office today to step straight from recuperation into crisis.”

The team news was that although Fred Davies and Ray Crawford were back in action, Ron Flowers (who had taken on the captaincy a year earlier after the departure of Bill Slater) was out injured and a decision was made to rest Jimmy Melia in favour of Peter Broadbent.

Cullis, who had not seen his team in action since the 3-2 loss at Filbert Street on 26th August, was upbeat on the subject of his health scare: “At least the tests I have had for the suspected virus infection and the subsequent examinations, followed by the rest, have shown me to be in good health.”

Morgan was blissfully unaware that the Wolves boss had been greeted on his return by John Ireland, who had taken over as chairman from Jim Marshall on 29th July. Ireland initially sought Cullis’ resignation on health grounds, but a predictable refusal left Ireland with no alternative but to sack the club’s most successful manager ever.

Keeping the discussion private, the returning boss led Wolves to a pulsating 4-3 win over a West Ham team that contained the eventual World Cup winning threesome of Bobby Moore, Martin Peters and Geoff Hurst. The FA Cup holders had handed out a thrashing at Upton Park just a week earlier and in any other circumstances the stirring match in which Wolves exacted some revenge would have lingered much longer in the memory for the right reasons.

Wanderers stormed into a two-goal lead within 34 minutes – first Ray Crawford headed in a Terry Wharton corner and then Peter Knowles drove home to allow himself an exuberant in-the-net celebration. However, when Peter Brabrook reduced the arrears six minutes before the break, it seemed that the miserable early season pattern might well continue, a fear confirmed when full-back Gerry Harris first turned a Brabrook effort into his own net and then conceded a penalty that Johnny Byrne converted around the hour mark.

But the committed club man was determined to go down fighting and with 13 minutes left he drove in a hard cross from the left-wing that rebounded off the chest of Jim Standen for Crawford to fire home the equaliser. Roared on by a relatively meagre crowd of 19,405, Harris then picked up the ball a few yards inside the Hammers half on the Molineux Street side and slammed in a shot that somehow eluded the cricketing goalkeeper to secure Wolves’ first win of the season.

Phil Morgan described it thus: “There has not been a more popular goal on the ground since Bill Shorthouse beat Sam Bartram, or a more vital one since Roy Swinbourne’s decider against Honved.”

Unfortunately, victory over West Ham did not change the decision that had been made earlier that afternoon and the dismissal that ended 30 years of unsurpassed service was made public on the Tuesday afternoon of 15th September.

The official statement from Molineux that day read: “The Wolves board of directors have informed their manager, Stanley Cullis, they wish to be released from their contractual arrangements with him. This he has consented to do.”

Phil Morgan reported the shocking news of the loss of a manager who, as recently as the club’s annual general meeting in August, had pledged: “I will never leave the Wolves unless I am sacked.”

Morgan’s article in the Express & Star was headlined, ‘Where do Wolves go now?’ and in reflecting on the career of ‘one of the greatest’ he speculated on the possibility of a two-manager arrangement. Claiming that it had begun to look “as though a rot had set in”, Morgan asserted that big money spent on the likes of Melia, Crawford and Woodruff had not really paid off whilst the flow of good youngsters was beginning to dry up as other clubs were increasingly prepared to do ‘under the counter’ deals; “Wolves abided by the rules and Cullis felt they were now paying the penalty.”

The strength of feeling in some that the sacking engenders to this day is summed up in the title ‘Betrayal’ that Jim Holden chose for the relevant chapter in his book, The Iron Manager. Whether it was Ireland’s own decision or that he was simply acting on behalf of the board remains an issue of contention. Derek Dougan always maintained that the wily Jim Marshall, believing that the legendary manager’s time was up, persuaded Ireland to become chairman at first for an interim period.

Dougan, who at one time lived near to Ireland in Wrottesley Road, commented: “I admire John Ireland so much – he was a wonderful director who wrongly took the flak and didn’t realise it.”

John Holsgrove concurs: “John Ireland was a wonderful chairman but they were bound to react this way to the man who sacked Stan Cullis. Bobby Thomson used to tell me all about Cullis, how hard he was. This man was God and he was sacked, but somebody had to draw the sword. It was somebody else’s time. I liked John Ireland. In 1965 he could have walked out on the club and they could have gone all the way down to the Fourth Division as they did in the eighties.”

Although John Richards fully understands the different views of some of the players who worked under Cullis, he argues that it was an unjust decision to later rename the Molineux Street Stand after Steve Bull and take away John Ireland’s honour.

Ken Hibbitt’s opinions are typical of his playing contemporaries: “John Ireland was a magnificent person – he never interfered. Of course, I don’t know what went on behind the scenes financially – it wasn’t for the players or me to understand that. You knew he worked hard for the football club. He was brilliant, all I remember is good things about John Ireland.”

In Steve Gordos’ book, Cullis Club and Country, Ireland’s daughter Shirley Jones revealed: “The board had agreed to it and it was up to father to do the deed. Mother said he hardly slept that weekend. He was walking around the garden in a dreadful state.” She added: “I’m quite sure Jimmy Marshall did not want to do it. He wanted father to be the one to do it.”

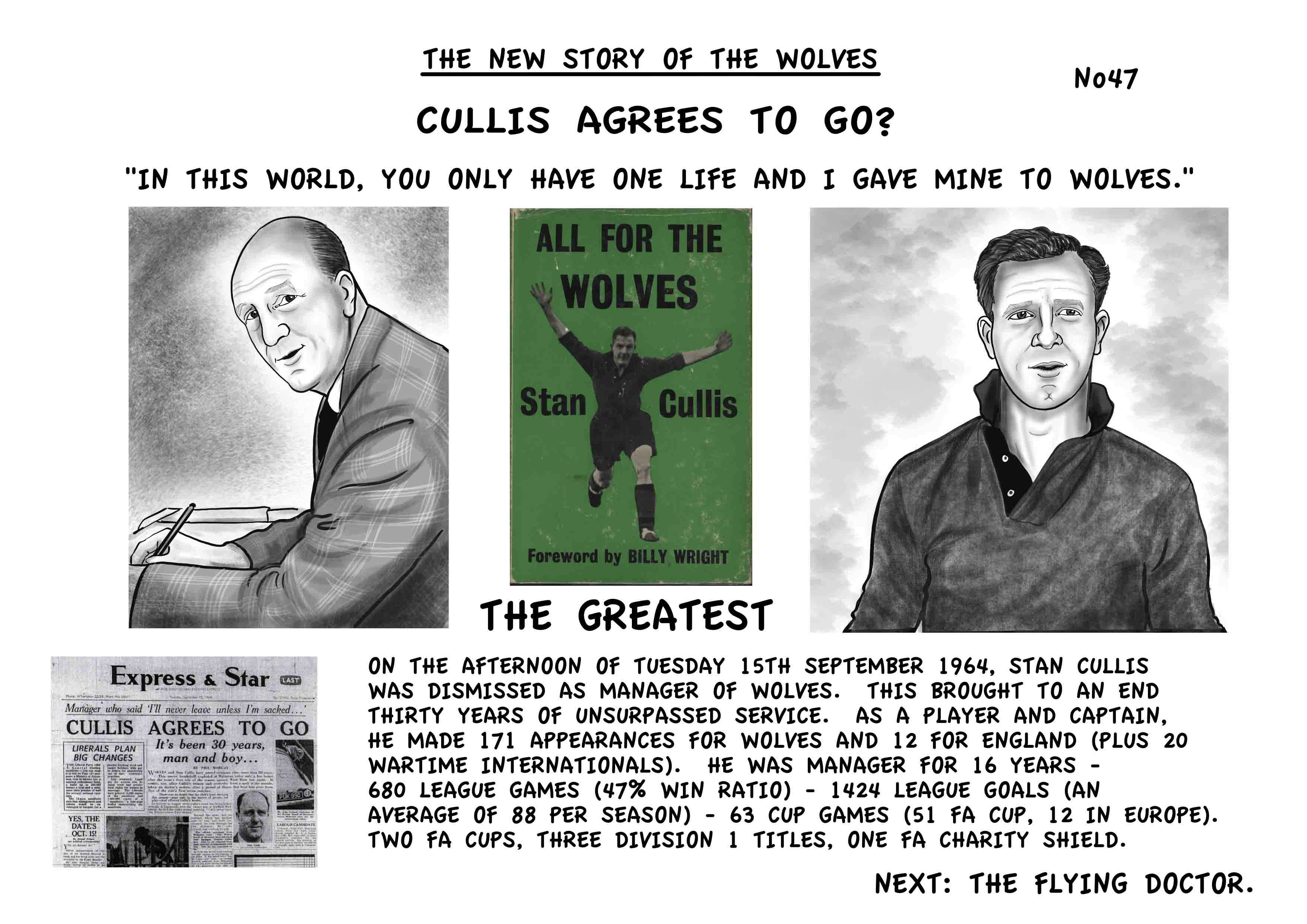

What is beyond dispute is the contribution of Cullis to his beloved Wolverhampton Wanderers. Having debuted on 16th February 1935, had the Second World War not intervened, Cullis would certainly have made more than 170 appearances for the club. He skippered the team for several years and narrowly missed out on honours, first the FA Cup in 1939 and then the Division 1 title in 1937/38, 1938/39 and 1946/47 seasons. He also captained England, by whom he was awarded 12 full caps.

Retiring in May 1947, Stan became assistant manager to Ted Vizard for the 1947/48 campaign and a year later began his reign as boss in his own right. In 1949, he guided Wolves to a first FA Cup final win in 41 years, following up with a first Division 1 title five years later. Two more top-flight triumphs were achieved in 1958 and 1959, alongside a second cup success in 1960 and a Charity Shield in 1960. Add to this three years of participation in fledging European competitions, allied to the floodlit matches at Molineux, and we have a record that is unlikely to be emulated.

He managed Wolves in 680 games over 16 years, winning almost half of those played and his team amassed an astonishing 1,424 league goals over this time. During Stan’s tenure Wolves also played 63 cup games. Fifteen months after leaving Wolves he became manager of Birmingham City, where he stayed until March 1970. Sir Jack Hayward named the new North Bank stand in honour of Stan Cullis in 1993. Cullis died in Malvern on 27th February 2001, aged 84. In 2003, he was inducted into the English Football Hall of Fame in recognition of his impact as a manager, but what would have been most special to Stan was the unveiling of a statue, on 14th June that same year. Of course, it still stands proudly behind the stand that bears his name.

Whom better to give the last word on a true Wolves legend but a man held in similar esteem in Liverpool? In his 1976 autobiography, Bill Shankly paid high tribute to Cullis, writing: "While Stan was volatile and outrageous in what he said, he never swore. And he could be as soft as mash. He would give you his last penny. Stan was 100 per cent Wolverhampton. His blood must have been of old gold. He would have died for Wolverhampton. Above all, Stan is a very clever man who could have been successful at anything. When he left Wolverhampton, I think his heart was broken and he thought the whole world had come down on top of him. All round, as a player, as a manager, and for general intelligence, it would be difficult to name anyone since the game began who could qualify to be in the same class as Stan Cullis.”