On a chilly December evening in 1954, 70 years ago today, Wolves etched their name into football history.

The English champions faced Hungarian juggernaut Honved, one of the greatest club teams of the era, under the dazzling Molineux floodlights and broadcast live on the BBC – a highly unusual occurrence at the time.

This game started a chain of events that would eventually lead to Real Madrid lifting their 15th Champions League trophy in London last May.

But how did this happen?

***

The summer of 1953 saw the first set of floodlights installed at Molineux. They comprised 60 lamps on four giant towers, with one floodlit pylon located at each corner of the ground.

Designed after the pattern used in New York’s famous Yankee Stadium, Wolves’ floodlights were officially switched on for the first time ahead of a friendly game against a South African XI on 30th September of that year, a game Wolves won 3-1.

That “International Floodlit Friendly” was the first of 14 matches which would be held at Molineux over the next four years and saw some of the biggest names in football arrive in the Black Country to play under the iconic lights.

At this time, Hungary’s national team, led by stars like Ferenc Puskas and Sandor Kocsis, was considered one of the best international sides ever assembled and had stunned England just a year earlier with a 6-3 demolition at Wembley – a game still remembered as a turning point in English football.

The Three Lions then suffered a 7-1 hammering away in Budapest, and at the heart of Hungary’s dominance was Honved, a club team boasting many of the country’s key players, including Puskas and Kocsis.

By the time Honved arrived at Molineux in December 1954, the team was filled with players who had Olympic gold medals and World Cup near-misses. Wolves, on the other hand, had just won their first English league title in 1953/54 and were topping the table once again.

The stage was set for a titanic clash.

A unique feature of the legendary night was the special shirts worn by the Wolves players under the floodlights. In anticipation of the high-profile evening matches, Wolves used a special set of gold jerseys made from a fluorescent material, designed to reflect the floodlights and make the players glow in the dark.

The shimmering effect was not only visually striking but also symbolic – Wolves were literally and figuratively shining on the grand stage. These shirts added an extra layer of spectacle to the occasion, making the team appear as though they were illuminated warriors battling in the mud, further fuelling the mystique of that unforgettable night.

What happened at Molineux that evening transcended a mere football contest.

The game ended up shaping the future of European football and solidified the Old Gold’s place as pioneers of the modern game.

Exactly 70 years on, this is the fascinating story of Wolves vs Honved.

Due to the friendlies which took place at Molineux between September 1953 and December 1954, Wolves became the pioneers of floodlit football.

Remaining unbeaten against teams from Argentina, Austria, South Africa, Scotland, Israel and the Soviet Union, when the Russians, in the shape of Spartak Moscow, arrived just a month before the Honved game, the Cold War was at its height.

To view Russian footballers in the Black Country would have been as unlikely as entertaining guests from the moon today.

But it was the Hungarians who had captured the heart of the nation as Honved arrived less than a fortnight before Christmas. BBC television cameras, which then only used to televise the FA Cup final, were at Molineux to bring the second half of the game into the homes of the British public.

In those days, the Black Country skyline was lit up at night by the white-hot fires from a myriad of foundries, but on the night of the Honved game, it was strangely dark, reminiscent of the blackout days of the war.

The perimeter of West Park, around a quarter of a mile from the ground, was encircled by motor coaches. This was not unusual in the days when Wolves were the front runners of English football, but their place of origin now had a national feel.

Long before motorways were built, coaches from as far afield as Somerset, Lincolnshire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, Gloucestershire, Leicestershire and Warwickshire arrived at Molineux. Meanwhile, in the main Waterloo Road stand, season ticket holders of many years’ standing were moved to accommodate the huge influx of FA officials and others in authority from both home and abroad.

They had all come to witness a huge footballing occasion.

Honved’s team was full of players who had become household names following the England/Hungary “Match of the Century” 13 months previously, as Puskas, Kocsis, Czibor, Bozsik, Lorant and Budai arrived in the West Midlands.

Meanwhile, the hosts had Williams, Slater, Wright, Flowers, Hancocks, Broadbent and Wilshaw, all who had either already played for their country or would shortly become England internationals. However, only skipper Billy Wright had played in those two devastating international defeats.

Before kick-off, the Honved players threw flowers into the crowd, a gesture not fully appreciated by all of the fans – many of whom on the cold night were still finishing their hot Bovril or Black Country pork scratchings.

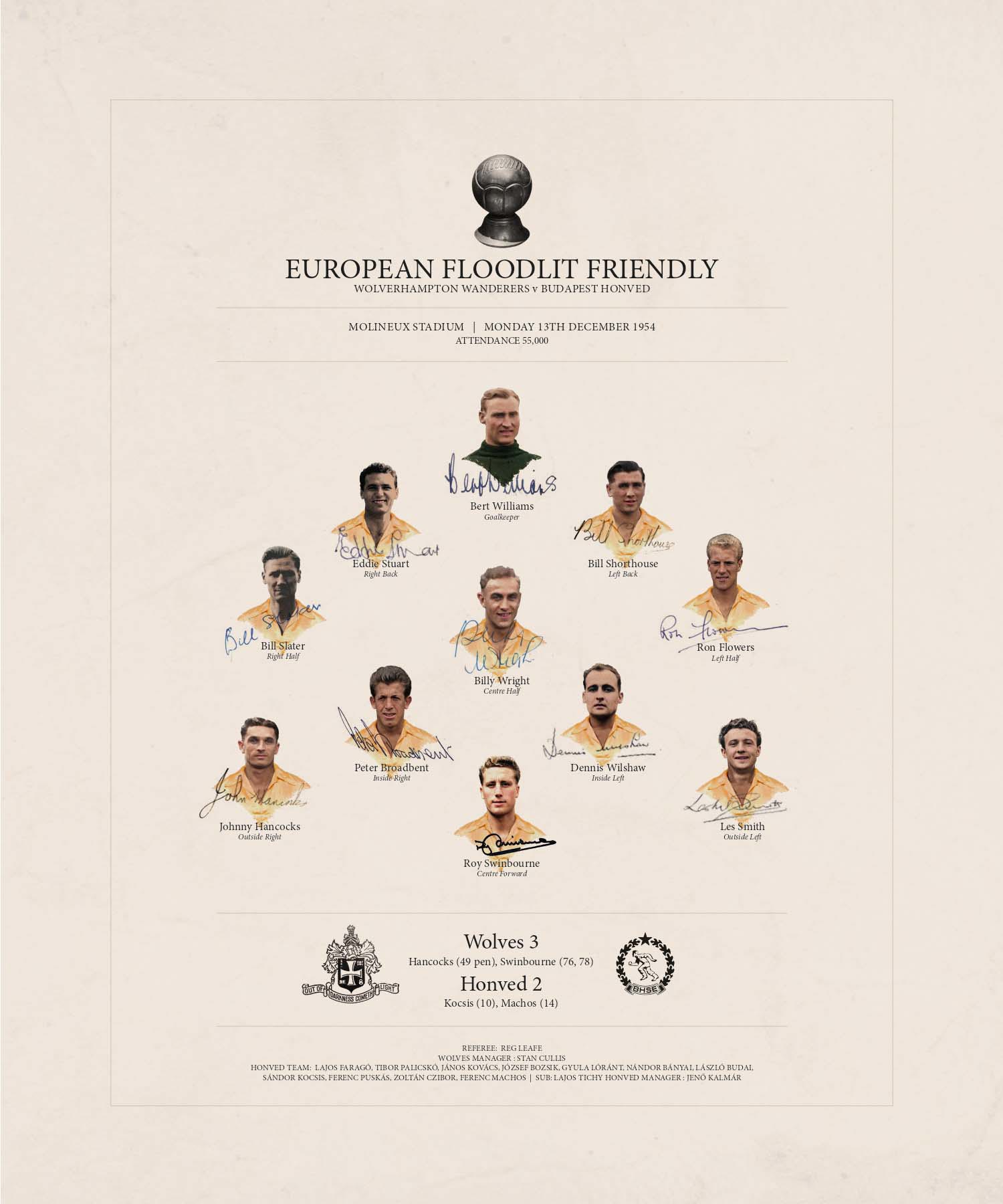

Wolves 3 (Hancocks 49 pen, Swinbourne 76, 78) Honved 2 (Kocsis 10, Machos 14)

Arguably the most famous match in Wolves’ history took place in front of a crowd just two people short of 55,000, paying the equivalent of between 12.5p and 52p.

Honved took the lead in the 10th minute when Sandor Kocsis, widely regarded as the best header of the ball on the continent, powered home a Ferenc Puskas free-kick. Four minutes later, Kocsis sent Ferenc Machos clear to beat Bert Williams with all the nonchalance of a training-ground routine.

By now, the massive crowd, so full of expectation just 15 minutes earlier, must have been fearing a footballing massacre of Hungary–England proportions. But the Wolves of that era were made of stronger stuff.

The hosts replied with a series of forceful counter-attacks and although they had not reduced the deficit by the interval, chances had been created for Ron Flowers, Peter Broadbent, Les Smith and Roy Swinbourne, only to be denied by keeper Lajos Farago.

Half-time | Wolves 0-2 Honved

Two goals down at the break, it would take an incredible comeback if Wolves were to get a result from the game.

But the hosts took inspiration from the rousing atmosphere of the evening, coupled with the fact that they were attacking the South Bank – a tradition which still continues today – and its heaving mass of 30,000 spectators, as well as giving the muddy Molineux surface a fresh soaking in an attempt to help slow down the free-flowing Hungarian football.

When the second period got underway, the national TV cameras were turned on as several million armchair well-wishers from across the country tuned in to add their support to that of the 55,000 present at Molineux – and they didn’t have to wait too long for the action to start up again.

Within four minutes of the restart, Johnny Hancocks was fouled by Janos Kovacs inside the penalty area. For a moment, the ear-splitting noise was silenced as Hancocks, one of the best penalty takers in the land, prepared to take the kick.

His shot was hard and true and Wolves were back in the game. Could the English champions revive the English game?

The excitement grew ever more frenetic as Honved were forced into an increasingly desperate retreat. Pressure on the visitors’ goal intensified, but Wolves still had to be on their guard, knowing full well how good their opponents were at breaking out of defence when least expected.

Broadbent began to find a lot more space in centre-midfield, Swinbourne got in two telling headers and Dennis Wilshaw had a piledriver tipped aside by the diving Farago. Then, with the time fast running out, Wolves went for the kill.

Lorant deliberately handled a cross to prevent Swinbourne having a clear shot at goal and then Hancocks almost bent the bar with a rocket from 20 yards. Flowers powered in a free-kick and Smith was narrowly wide with a snapshot after being set up by Broadbent.

There were signs that Honved’s defence was beginning to crack – and crack it did with just 14 minutes remaining.

Bill Slater found Wilshaw, who centred for Swinbourne to nod home past the helpless Farago. Moments later, Wilshaw sent Smith away down the left wing. He slipped the ball inside, into the path of Swinbourne, who was having a splendid game. The centre-forward ran on to power home his second goal.

Honved fought back and Zoltan Czibor, recognised as one of the fastest wingers in the world, broke through, only for Bert Williams to smother his shot.

Somehow, Wolves held on to beat the then-best footballing side ever seen at Molineux – and those present would never forget what they saw on that evening in 1954.

Full-time | Wolves 3-2 Honved

Wolves: Williams, Stuart, Shorthouse, Slater, Wright, Flowers, Hancocks, Broadbent, Swinbourne, Wilshaw, Smith.

Honved: Farago, Palicsko, Kovacs, Bozsik, Lorant, Banyai, Budai, Kocsis, Machos (Tichy 84), Puskas, Czibor.

Referee: Reg Leafe (Nottingham)

Attendance: 54,998

The final whistle prompted huge celebrations, which stirred Peter Wilson, chief football writer of the Daily Mirror, to note: “I may never live to see a greater thriller than this. And if I see many more as thrilling as this I may not live much longer anyway.”

The impact upon the British public was summed up by George Best, a boyhood Wolves fan, who described the match as “fantastic, but it was the floodlights which made football magical for me. There was just an extra-special feeling about a game being played in the evening. It was sheer theatre.”

Wolves manager Stan Cullis, who had called his players “the champions of the world”, said: “The match was the most exciting I have ever seen. I had a chat with Billy Wright at half-time and after that he and the rest of the team were inspired.”

Wright added: “It was good to gain revenge for England’s defeat at Wembley and it was a wonderful achievement by a wonderful team.”

Dennis Wilshaw described it as: “The greatest game in which I have ever played.” Bert Williams summed up the game by saying: “That night against Honved must have been one of the ten greatest matches ever played in the history of football.”

While Roy Swinbourne, Wolves’ goalscoring hero that evening, reflected: “Wolves never played a match in which there was so much pride involved as there was in the Honved game.”

Gustav Sebes, coach of the Hungarian national side, commented laconically: “We were beaten. That is all there is to know.”

Following full-time, Charles Buchan, the former Arsenal and England star who had become a much-respected journalist, said: “Wolves struck another decisive blow for British football with as wonderful a second-half rally as I have seen in forty years.”

But the final, poetic, word goes to Geoffrey Green, Times correspondent: “Bit by bit Wolves began to turn the screws. Their shirts of old gold, trimmed with black at the edges and specially treated with luminous effect for night matches, began to fill the dark field. The Molineux crowd surged, tossed and roared like a hurricane at sea, and called for the kill.”

However, Green’s words are wrong on three counts – the shirts were gold (not old gold), there was no black trim and they were not treated with anything!

The sight of Wolves toppling one of the greatest teams in the world left an indelible mark on the footballing landscape. With their 3-2 win over Honved, not only had Wolves earned a famous victory, but they had set the cogs in place for the future of European football.

The game is not only iconic for Wolves and British football but proved to be the catalyst for the formation of the European Cup, the forerunner of the Champions League.

Following the match, some English newspapers – including the Daily Mail – quoted the words of Cullis and declared Wolves to be “champions of the world”.

However, Gabriel Hanot of L’Equipe, thought this a premature claim and published plans for a European Cup after he had long been campaigning for a continental club competition.

Hanot responded to the British press by saying: “Before we declare that Wolverhampton Wanderers are invincible, let them go to Moscow and Budapest. And there are other internationally renowned clubs: AC Milan and Real Madrid to name but two. A club world championship, or at least a European one – larger, more meaningful and more prestigious than the Mitropa Cup and more original than a competition for national teams – should be launched.”

Wolves’ victory over Honved, coupled with the media storm that was created, rejuvenated the idea of a continental club competition, gave it more impetus and made sure proposals which had been raised for the previous three decades finally became a reality.

In March 1955, just three months after Wolves’ win over Honved, a UEFA congress met in Paris where the proposal was made official and the formation of the first ever European Champion Clubs’ Cup was agreed.

The Honved victory remains one of the most cherished moments in Wolves’ rich history. It wasn’t just about beating a great team, but about showcasing British football on a global stage and igniting the spark that would lead to the formation of Europe’s most prestigious club competition.

In the decades that followed, Wolves would go on to compete in the European Cup and other continental competitions, but it is that magical night in 1954 that still resonates the most.

It was the night when Wolves, under the lights of Molineux, proved that they could compete with the best in the world. The game laid the foundation for European football we know today and remains a proud chapter in the story of Wolverhampton Wanderers.

As we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the iconic game, we remember not only a match but a moment that changed the face of football forever.

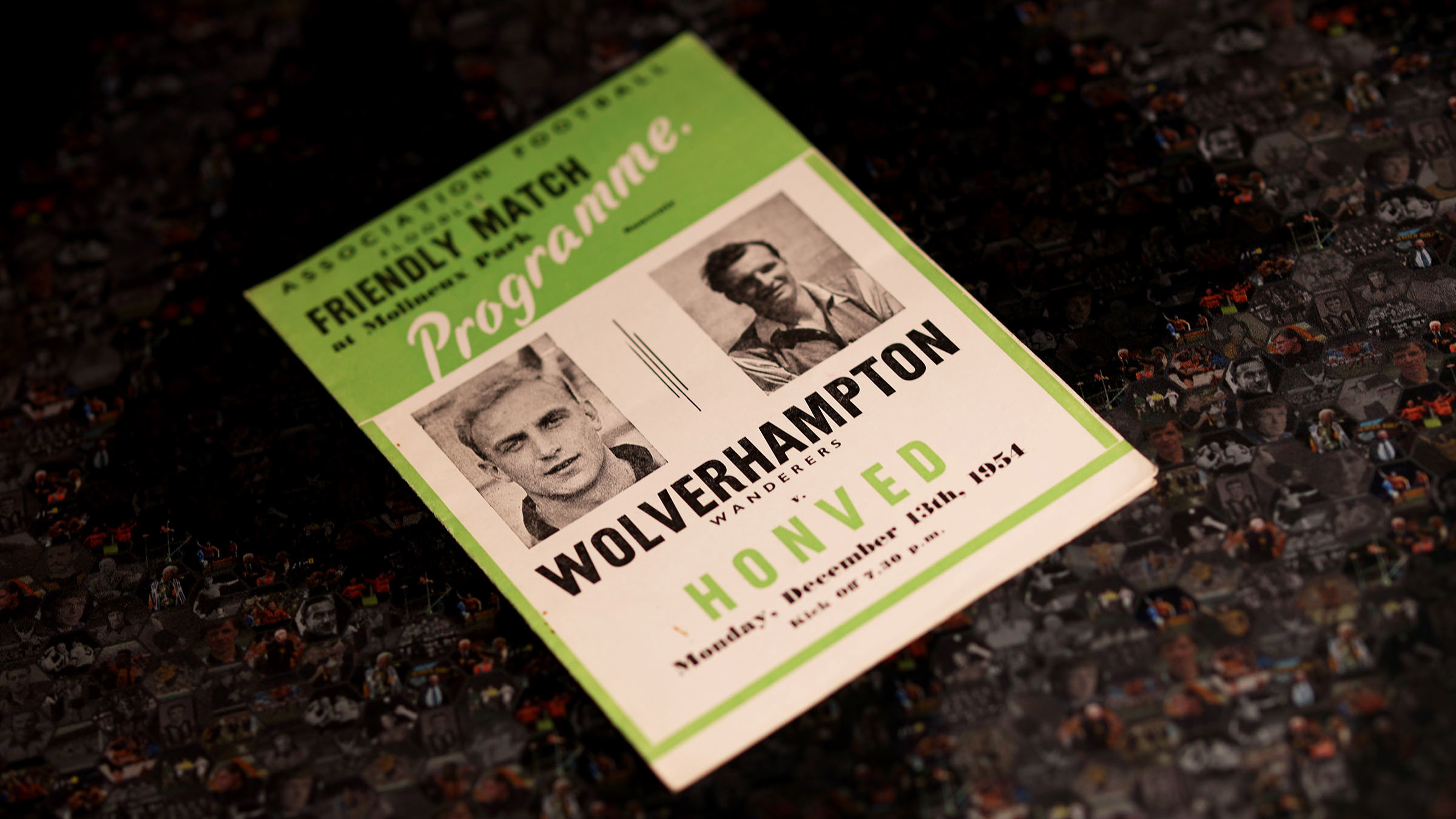

A 100-page souvenir edition of the official matchday programme has been created to commemorate the 70-year anniversary of the Honved match at Saturday's Premier League game with Ipswich Town.

The special edition programme is available by clicking here or from around Molineux on a matchday. A yearly programme subscription for the whole 2024/25 season is also available by clicking here.